A History of HIV/AIDS

The history of HIV/AIDS in Washington, which continues to unfold through the present day, is decades-long and vast, filled with countless players and innumerable events. The following is an overview of HIV/AIDS in our region.

1982

HIV in Washington

Signs of AIDS preceded the first diagnosed case in Seattle in November 1982, but Seattle never received the kind of attention around “gay cancer” or GRID (Gay-Related Immuno-Deficiency) that Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York did.

AIDS was known, named, and linked to gay men by the time the first case received attention in Seattle. The city council promptly set aside funds for AIDS treatment and research, becoming the second municipality in the United States to do so, in 1983.[1]

Mid 1980s

Women and Activism

During the 1980s, gender divisions softened and more lesbian spaces, including communal houses, opened on and around Capitol Hill. Many lesbians became involved in AIDS activism, often as caregivers for sick gay men, as volunteers for the Chicken Soup Brigade, and as leaders of community organizations. Women founded and led organizations such as POCAAN, the Chicken Soup Brigade, and Bailey-Boushay House.

In the mid-80s, the Northwest AIDS Foundation (NWAF) gained a seat at the table with Seattle-King County Public Health (SKCDPH) and received funding from SKCDPH for outreach in the gay community.

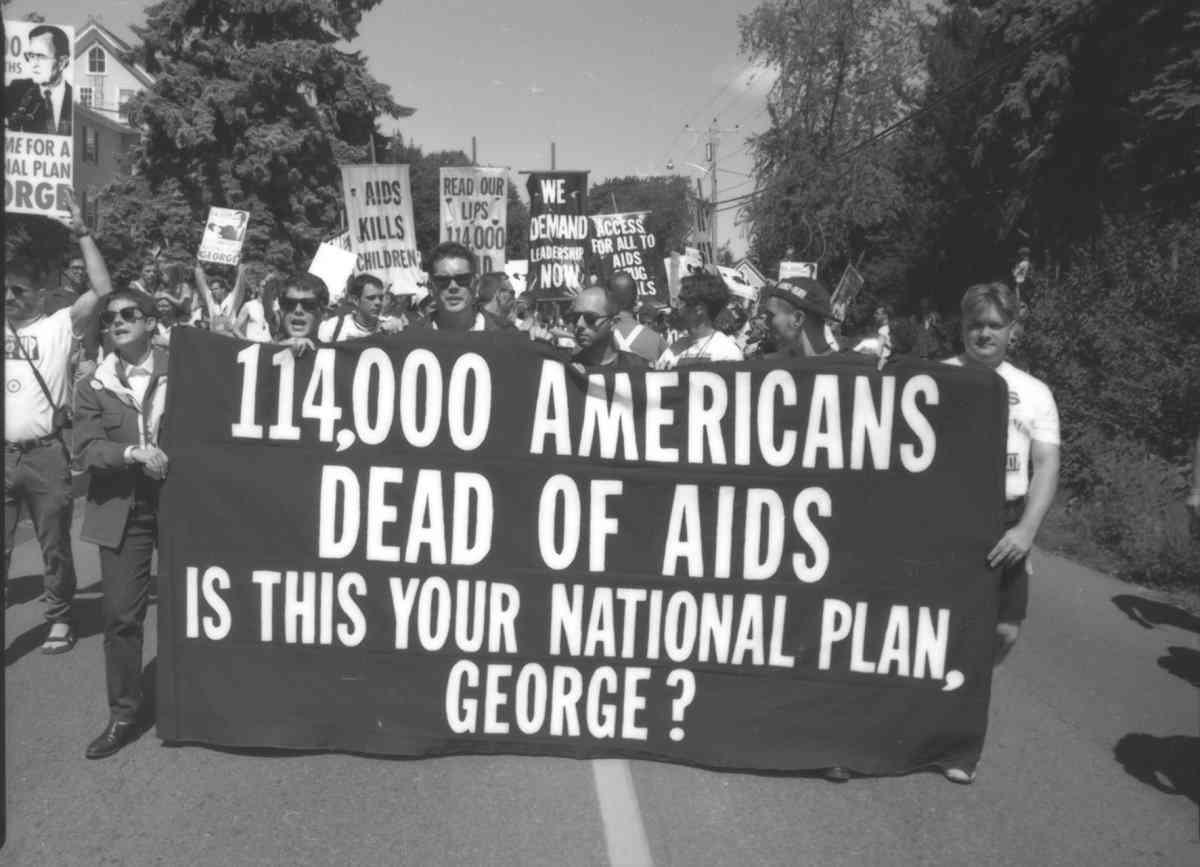

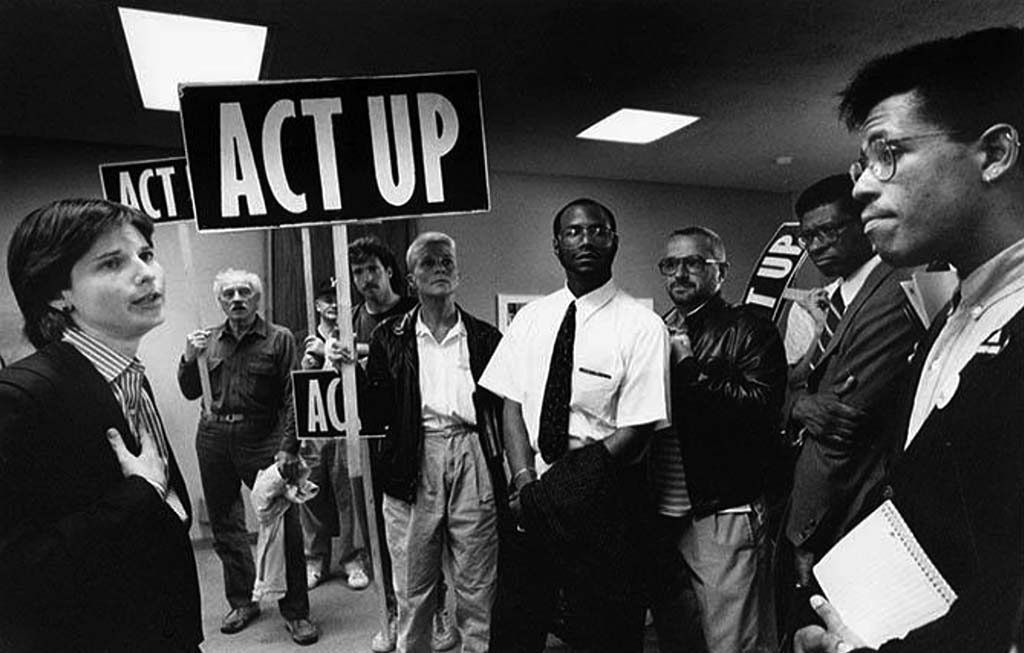

ACTUP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) first formed in New York City in 1987 as a radical protest organization seeking to change AIDS policies and draw more public attention and funds to AIDS research. The ACTUP Seattle chapter was quite active by decade’s end. For example, they picketed centers holding clinical trials for AIDS treatment and harassed city officials, demanding quicker trials and faster policy relief.

Mid 1980s

Raising Awareness, Raising Funds

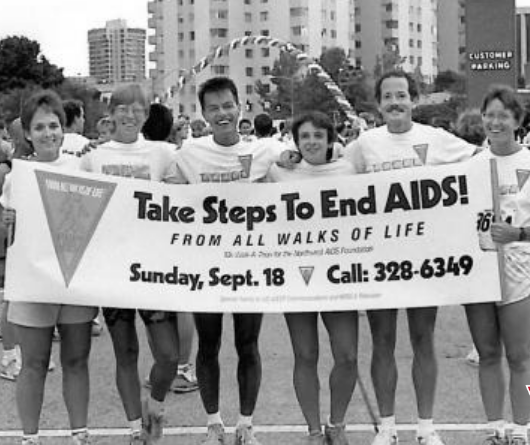

In 1986 the Northwest AIDS Foundation initiated a powerful effort to draw attention to the AIDS crisis – the Northwest AIDS Walk, From All Walks of Life. The idea started with a sister organization in Boston willing to share its experience, just as AIDS organizations around the country generously shared what they learned in the early days. Initially, the cost of mounting the walk took one-third of NWAF’s funds on hand – a huge risk for a young organization.

The risk paid off. Each September, corporate and political leaders joined media personalities and walk teams from the many communities affected by AIDS. By the fifth annual walk, the event drew 13,000 concerned people to the streets and raised $1.2 million for 30 organizations providing AIDS education and services.

In addition to the tremendously visible Walk, other grassroots fundraising brought in much needed dollars for AIDS services, including Jars in Bars, the Bunny Brigade, and the perennial and popular events by the Tacky Tourist Club.

Late 1980s

Communities Coming Together

People of color responded to AIDS by forming organizations focusing on non-white AIDS patients. One of the major groups was the People of Color Against AIDS Network (POCAAN), established in 1987. Like NWAF, POCAAN received funding from SKCDPH for outreach to communities of color. The main goal of POCAAN was to educate gay men of color about safe sex, AIDS awareness, and treatment. These groups provided a space where gay people of color and AIDS patients could feel culturally welcomed. Specifically, Entre Hermanos addressed its audience in Spanish and English while also combating homophobia in Latinx culture.[1]

Late 1980s

Political Changes

Cal Anderson became the first gay member of the Washington state legislature when he was appointed in 1987 to serve Seattle’s 43rd District (central Seattle) in the state House of Representatives. He won election to the state senate in 1994 but served less than one year before dying of complications related to AIDS.

In early 1988, the state legislature, acting on recommendations from the Governor’s Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, considered legislation to protect the civil rights of people living with HIV. The proposal also sought to mandate AIDS education in state schools, beginning in the fifth grade, with an emphasis on sexual abstinence (1988 Wash. Laws). To calm potential parental blowback, school districts would be required to make materials available to parents and guardians before AIDS-centered lessons were taught. The state’s workforce would also receive education. Known as the AIDS Omnibus Act, it passed the state legislature by one vote.

Lobbyists, including the American Civil Liberties Union, considered it a success. Other states used it as a model, as it was viewed by many as the most progressive AIDS-centered legislation during that era. Nestled in its 25 pages was a state-assured guarantee that no one would be tested for HIV without consent — unless, as stipulated in a list of exemptions, the person was convicted of a sex offense. In short order, Washingtonians would witness how this requirement would play out.[2]

Late 1980s

Needle Exchange Starts in Tacoma

The world’s first needle exchange programs appeared in 1983 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, instituted by local health officials when a pharmacy stopped selling sterile needles and syringes to IV drug users. Shown to lower HIV rates, legal exchange programs arose in other countries. Not so in the U.S. — until a Tacoma man named Dave Purchase started a program in August 1988 by placing a folding chair and TV tray close to a house known to draw heroin users. He exchanged needles for free. It’s considered the first legal and publicly funded needle exchange program in the country and was soon supported by the Pierce County Health Department.

ACT UP Seattle members heard what Purchase had done in Tacoma and decided to apply similar tactics in the Emerald City. There was one problem: exchanging used needles for clean ones without a prescription was illegal.

To activists, however, potentially saving lives overrode legality. In March 1989, ACT UP Seattle set up a needle-exchange table downtown that moved from location to location, not only to offer access to as many injection drug users as possible, but to evade police. Local public health officials knew the exchange program was in full swing, and some had even given it their blessing. Even so, they reasoned that they themselves should run any needle exchange program. ACT UP agreed — it didn’t exist to provide services the government should be furnishing. Within a couple of months, the health department secured county funding and took over the program. Within years, local needle exchange annual volume surpassed 500,000 syringes.[2]

Early 1990s

Bailey-Boushay House

In 1991, 321 people died of AIDS-related complications in King County. The ongoing death toll, contextualized with research funded by the public health department’s 1986 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant, demonstrated the need for AIDS hospice care. Volunteers created AIDS Housing of Washington, and located a promising site on a major roadway in Madison Valley, where a 35-bed nursing facility was planned. Money was raised. But the project faced a major roadblock: opposition from neighbors.

When community members learned one of the leading developers opposed to the facility was president of the board of the Seattle Art Museum, ACT UP Seattle planned to protest the museum’s upcoming gala. Museum staff tried, but failed, to convince activists to cancel their planned action. Instead, the developers caved, the activists celebrated, and the facility was built. Operated by Virginia Mason Hospital, Bailey-Boushay House opened on June 24, 1992. It was the nation’s first long-term care facility and outpatient health program for people living with AIDS in the country.[2]

Mid 1990s

Introduction of Effective Therapies

An AIDS hospice, a needle exchange program, statewide legislation protecting (most) people living with AIDS: Washington had scored multiple wins. But larger, nationwide victories were on the horizon.

In 1994, researchers announced that HIV transmission from mother to infant had been reduced when mothers used AZT, a controversial drug that local people living with AIDS had tested in early trials. The same year, saquinavir, a type of drug known as a protease inhibitor which prevents viral replication, was approved for people living with HIV. Medication, while not always affordable, was available. In 1996, the CDC announced its first decline in AIDS-related deaths since it began gathering data.

The nationwide epidemic had peaked — at least for some. AIDS still had its tenterhooks in the lives of women, people of color, and injection drug users. Globally, HIV/AIDS had become the world’s fourth-leading cause of death.[2]

Since 2010

Current Treatment

By 2010, there were up to 20 different treatment options as well as generic drugs, which helped lower costs.

As of 2017, studies have shown that a person living with HIV who is on regular antiretroviral therapy, which reduces the virus to undetectable levels in the blood, is NOT able to transmit HIV to a partner during sex. The current consensus among medical professionals is that “undetectable = untransmittable.”[3]

Today

Washington State

By 2018, the AIDS crisis had claimed 8,043 lives in Washington state, and more than 14,000 people were living with HIV. Roughly 90 percent of those were aware of their status, including in King County, which had achieved a medical milestone known as “90-90-90”: 90 percent of residents knew their status, 90 percent of that group were taking antiretrovirals, and 90 percent of that group had suppressed viral counts. King County was one of the first regions — if not the first — in the country to reach that goal.[2]

Historical Groups

There were many organizations and community efforts that contributed greatly to the fight against AIDS, and that supported HIV+ individuals.

Some of these groups are still active with broader missions, or became part of currently active organizations:

- AIDS Housing of Washington, 1983-2009 (became Building Changes)

- Chicken Soup Brigade, 1983-present (became part of Lifelong)

- The Natural Health Clinic of Bastyr University

- Northwest AIDS Foundation, 1983-2001 (became Lifelong)

- SASG (Seattle AIDS Support Group), 1984-2018 (became Peer Seattle)

- Seattle Gay Clinic, 1979-2004 (became part of Gay City)

- Country Doctor Community Clinic

- Downtown Emergency Services Center (DESC)

- UW Medical Center/Roosevelt, Virology Clinic

Many are no longer active but left a lasting mark with the work they achieved:

- ACT UP Seattle (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power)

- AIDS/HIV Care Access Project (ACAP)

- Bunny Brigade

- Cascade AIDS Project (serves Clark County)

- In Touch

- Jars in Bars (Lenny Larson)

- Kang Wen Clinic

- MAPS

- Northwest Family Center (NWFC)

- Rosehedge/Multifaith Works (1988-2013)

- Seattle AIDS Action Committee

- Shanti

- STEP (Seattle Treatment Education Project)

- Stonewall Recovery Services

- Street Outreach Services (SOS)

- United Communities AIDS Network (UCAN)

- Volunteer Attorneys for People with AIDS (VAPWA)

References:

1. Kevin McKenna and Michael Aguirre, “A brief history of LGBTQ Activism in Seattle”

2. Rosette Royale, “HIV/AIDS in Western Washington”

3. CDC online

In remembrance of those we've lost to HIV/AIDS

Finding and reading a name can help you connect with personal memories. The collection of names can show the vast impact of HIV/AIDS.